"You Had Me at Seaweed and Champagne"

Reflections on blue foods, aquaculture, regenerative food systems, and a surprising night of pairings that challenged old assumptions about wine and seafood.

Gathered inside St. Supéry Estate Vineyards & Winery, a handful of us came together for an unusually intimate event — a special “Friends of the House” session of Master Sommelier Andrea Robinson’s Quench Live program, featuring culinary legend and sustainability advocate Andrew Zimmern, beamed in virtually for a conversation about blue foods, sustainable seafood, and their intersection with responsible winegrowing. This was Where’s the Reef! — a discussion about where our food comes from, and how our choices connect to ecosystems and communities far beyond the plate.

The conversation centered around the global movement toward blue foods, foods sourced from aquatic ecosystems, which feed 3.2 billion people every day. As emphasized in this incredible conversation, sustainably managed waters, marine protected areas, and responsible aquaculture will play a significant role in feeding the world within planetary boundaries, the ecological thresholds that keep our climate, biodiversity, soils, and oceans stable enough for life to thrive. Crossing these boundaries pushes ecosystems past tipping points; operating within them supports long-term resilience.

We discussed lessons from Hope in the Water, a PBS series exploring the future of seafood, produced with the support of Fed by Blue, a non-profit initiative dedicated to education and activism around sustainable blue-food systems; bridging scientists, chefs, policy makers, and consumers to shift cultural understanding of the ocean as a food source. The documentary series confronts outdated assumptions concerning fresh vs. frozen, wild vs. farmed, and highlights the true modern sustainability questions such as:

Not “what’s wild?” but “what’s well-managed?”

Frozen fish, when processed and flash-frozen immediately after harvest, can arrive at its destination in peak condition. By contrast, “fresh” fish that travels by truck or air freight may spend days in distribution before reaching a market, degrading texture and flavor along the way.

Farmed seafood isn’t the villain, however; irresponsible farming is, such as operations that overuse antibiotics, pollute local waters with waste, or introduce escaped non-native species into wild ecosystems. Responsible aquaculture, on the other hand, uses well-managed environments and careful waste cycling to reduce ecological impact.

One striking narrative from Hope in the Water explored the Vietnamese shrimp industry as an example of how aquaculture can either degrade ecosystems or help restore them. Shrimp is one of the most consumed seafoods on the planet, with nearly two-thirds of global shrimp production coming from farming. Vietnam, one of the largest shrimp exporters, produces over one million tons annually, supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs and generating billions in revenue. But much of this boom came at a cost: large swaths of ecologically critical mangroves, natural nurseries for marine life and buffers against coastal erosion, were destroyed to build shrimp ponds.

Vietnam eventually made mangrove destruction illegal, recognizing that environmental protection and economic opportunity should not be mutually exclusive. Poorly managed shrimp farms saw disease devastate ponds, illustrating the consequences of imbalance. But other farms, including models like ShrimpVet Farm, began pioneering circular, polyculture systems that treat waste, reduce pathogen risk, and incorporate mangrove recovery.

Just as Vietnam has had to confront the cost of extractive aquaculture and move toward more regenerative practices, food systems on land face similar choices. Industrialized livestock production, especially concentrated animal feeding operations, can be extremely resource-intensive, demanding significant land, water, and chemical inputs, and generating waste and greenhouse gases. At the same time, there are ranchers working with regenerative and holistic best management practices: rotational grazing, living forage, soil-building, and improved animal wellbeing. This discussion led naturally into the role of winemaking and viticulture as part of the same systems thinking; in vineyard settings, livestock can play an active role in cover crop management, nutrient cycling, and weed control, creating symbiotic benefits between animals, vines, and soil health.

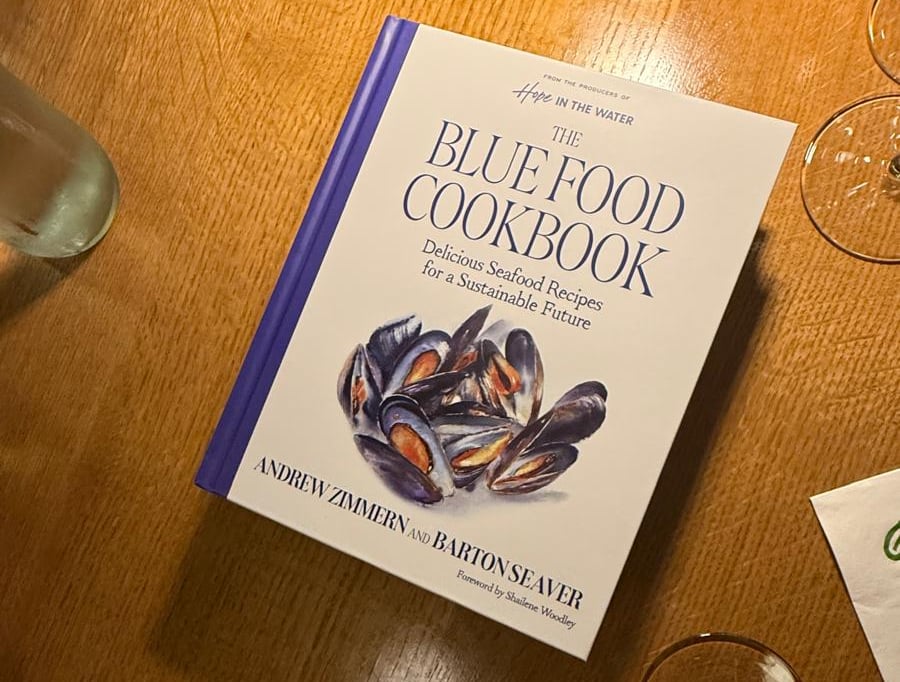

Jennifer Bushman, Executive Director of Fed by Blue, was with us in person, helping frame the evening’s insights and offering real‑world context from the frontlines of sustainable seafood advocacy. She walked us through Seafood Scout, a new platform that helps consumers trace where their seafood comes from, who harvested it, how it was raised or caught, and whether it meets vetted sustainability standards, empowering people to make choices rooted in transparency and accountability. While the conversation unfolded, we were treated to a menu built from The Blue Food Cookbook, a collection of recipes and contributions from a global network of chefs dedicated to sustainable seafood systems.

“You had me at seaweed and Champagne.” Andrea tossed this line out with a laugh, and it stuck with me because pairing sea vegetables with sparkling wine reflects a deeper truth: when we protect and nurture the environments where these foods originate, the kelp beds, reefs, tidal ecosystems, and likewise, the vineyard soils, beneficial insect corridors, and riparian buffers, we end up with ingredients, and wines, that express purity, balance, and a sense of place.

Sea vegetables, kelp forests, and bivalves — nature’s water filters — are poised to become some of the most vital foods on the planet because they require no freshwater, no fertilizer, no feed inputs, and actively improve the ecosystems they inhabit. Kelp draws down carbon and nitrogen; bivalves filter and clean the water column; both of these organisms improve ecosystem function as they grow and when responsibly managed, add net ecological value.

As CEO of St. Supéry, Emma Swain offered a simple framing that grounded the evening: “What pairs best with great sustainable wine? Sustainable seafood.” It wasn’t just a line, but rather it was a guiding principle for how St. Supéry approaches land stewardship, transparency, and culinary harmony. St. Supéry embodies this through solar power usage, compost integration, beneficial insect support plantings, and onsite ecological stewardship.

With each dish came a thoughtfully chosen St. Supéry wine — all estate‑grown and certified through the Napa Green Vineyard & Winery programs. Napa Green certification goes beyond intention; it requires measurable practices in water conservation, pollution prevention, carbon footprint reduction, waste reduction, and habitat preservation.

And fittingly, the pairings themselves reflected that same thoughtful approach. For decades, the conventional wisdom in American wine culture was that white wine goes with fish and red wine goes with meat, a simplistic rule that ignored texture, fat content, smokiness, salinity, and umami. This evening put that old red-with-meat / white-with-fish myth in the compost bin: wine pairing is about structure — salt, acid, fat, and the weight each component carries.

Course 1 — “Fish & Chips, But Make It Salad” Little gems, tomatoes, Persian cucumbers, russet potato chips, and smoky tinned trout came together in a salad that was far more complex than its name implied. The 2023 Dollarhide Estate Sauvignon Blanc lifted every bright, crisp element of the dish, with grapefruit lighting up the cucumbers, the fresh snap of the tomato complementing the citrus notes, and the wine’s minerality and subtle saline imprint meeting the fat and salt of the potato chips — tying together every element from brightness to brine to the soft smokiness of the trout.

Then came the unexpected pairing suggestion: Andrea recommended tasting the salad with the 2019 Élu, a Cabernet-based Bordeaux blend. It worked far better than conventional wine rules would predict. The salty chips softened the tannin. The smoky trout mirrored the wine’s espresso and toasty-oak notes. Petit Verdot’s aromatic lift and spice found harmony with the smoky trout, bringing balance to the pairing.

It was a subtle, delicious dismantling of the old 20th-century pairing doctrine that "red wine doesn’t go with fish."

Course 2 — Tsar Nicoulai Grilled Sturgeon with Masala Tomato Sauce The sturgeon came from Tsar Nicoulai — America’s only ECOCERT™-certified sturgeon farm — where the fish are raised in California’s Sacramento Valley in a system that recycles up to 90% of its water and uses no antibiotics or growth hormones. Prepared with gochugaru, coconut milk, shallot, and mint, this dish was warm, aromatic, layered. The 2023 Estate Virtú (Sauvignon Blanc & Sémillon) bridged brightness and texture, connecting to the curry and coconut notes effortlessly. The Élu again found its place, this time aligning with char, spice, and savory depth.

Dessert — Brownies with Dulse (Seaweed) These brownies were not candy-sweet; they were mineral, deep, elegant. Dulse, a red seaweed, added umami and salinity that allowed the 2019 Dollarhide Cabernet Sauvignon to shine rather than clash with cocoa.

One of Andrea’s refrains stayed with me long after the plates were cleared: “Every choice is a choice. And if you’re lucky enough to be able to make choices, make them good ones.”

Though only eight of us sat together in the room, the conversation felt global. We felt connected not just to the wines and dishes in front of us, but to the reefs, waters, fishermen, kelp farmers, vintners, and ecosystems behind them.

It reminded me that sustainability is not just policy or certification, it’s community, flavor, and story. And sometimes, it’s a salad, a smoky tin of trout, and a glass of Élu teaching you that the world is far more delicious when you let go of old rules.